Holi, the Hindu Festival of Colors, is a cheerful and joyous celebration of prosperity and well-being. Aside from being celebrated widely in India, it is also quite popular in the Caribbean colonies which have a large populations of Hindus. Over the past few decades, the global Hindu diaspora has made this festival popular in Western countries as well, welcoming local non-Hindus in the revelry. It’s hard to resist, with its stunning, vibrant visuals and community spirit. Without understanding its roots and appreciating the intent of the festival, however, an indigenous festival like Holi can easily lose the beautiful depth of its reverence and morph into an exotic caricature. Even worse, xenophobic and ignorant myths are often written over the authentic significance of these holidays.

Let’s take a moment to explore the Festival of Colors, so we can fully honor its spirit of love, celebration, reverence, and community.

Women Whipping Men with Clothes for Holi, Shri Dauji Temple, Uttar Pradesh India. (Picture Credits: Adam Cohen | Flickr)

Holi is celebrated in the spring, which is a very auspicious season for Hindus from all over India. Other important springtime festivals include Basant Panchami, Shivaratri, Ugadi, and Rama Navami. In the largely agrarian communities of North India, Holi, also known as Phagwa, is perhaps the most widely celebrated springtime festival. The Holi bonfire is lit on the Purnima (full-moon night) of the Phalgun month of the Hindu luni-solar calendar and the celebration with colors happens on the next day. Holi’s special popularity in North India, is partly due to its unique timing in the spring, a few days before the vernal equinox, when the wheat harvest is at the peak of its maturity, making Holi, the beginning of a month long festivity which includes the Hindu New Year.

Crooke, notes of Holi celebrations in 1914, "This at present, from the eccentricity of the Hindu luni- solar calendar, does not, in Northern India, represent a well-defined agricultural season. The wheat and other crops of the cold-weather harvest are sown about October, at the close of the rainy season; wheat in the Panjab is reaped from about the end of April to the beginning of June, while in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh the harvest is finished in March-April. The Holi thus takes place when the most important crops of the spring harvest are approaching maturity. It is a time of leisure from field work. The Hindu poets never tire of describing the spring as a period of rejoicing, and this time when the sun is moving northward in the heavens is the season for marriages.” [1]

Holi in Nandgaon, Brij Mathura (Picture Credits: Saurabh Chatterjee | Flickr)

Holi also finds numerous mentions in the life stories of Sri Krishna, and thus has a very special association with the various Vaishnava Bhakti traditions. The significance of Holi in Sri Krishna Bhakti traditions and the unique 7-day Holi of Vrindavan and Nandgaon, the birth place of Shri Krishna is very well documented. Thus, we shall focus on the more rural and tribal celebrations of the North Indian agrarian society, which is not as widely known.

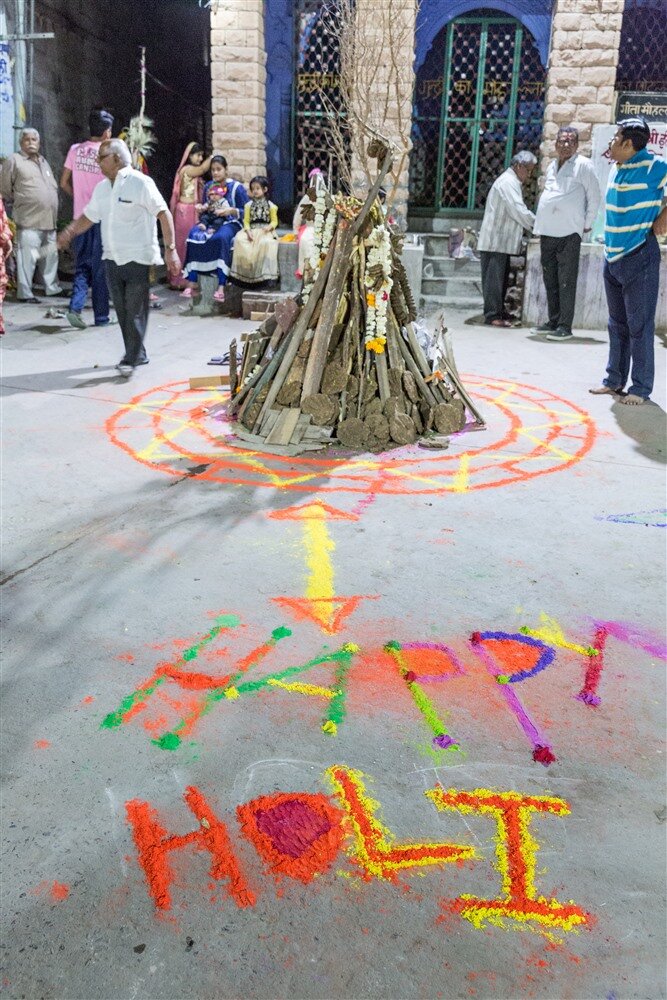

Holi Bonfire - “Chhoti Holi”

The Holi celebration has two parts. The first is the day of the bonfire, “Holika Dahan” (the burning of Holika), also known as “Chhoti Holi”. Householders wear new clothes, clean their houses, and take ritual baths on the this day. Mud-huts are freshly coated and decorations are drawn on the walls and front of homes. Household trash is removed and taken to the ritual bonfire at night. This offering to the bonfire symbolizes the banishment of evil from homes. Because of its connection to the agricultural season, the Holi bonfire is also regarded as a harvest festival. Farming families pray for a healthy crop and protection from all evil, just as Lord Vishnu’s devotee Prahlada was protected against evil.

Holika Dahan, or Holi bonfire in a semi-urban town in India. Source: Reuters

People gather around the bonfire, often singing folk songs in Prakrit-based local rural languages and regional dialects, such as Brij, Awadhi, Bhojpuri and Maithili, rather than Sanskrit, a more priestly language. In fact, an entire genre of agrarian folk music exists around the festival of Holi, known as Phagwa (Phaag or Phagan) songs whose primary themes are not just the Holi festival and associated Gods but also crops, love and relationships, nature, community and the joy of spring. These songs are especially popular in the agrarian swathes of UP-Bihar states of North India.

Malini Awasthi performs “Hori Phagunva me rang ras ras barse”, a traditional Awadhi Phaagun folk song. (Music of Uttar Pradesh)

We can see parallels for the sacred Holi bonfire in several other nature-worshipping indigenous traditions. Indigenous tribes of the Americas, Australia and even the paganic tribes of pre-Christian Europe often celebrate bonfires in and around harvest season. They are considered to have an apotropaic (averting evil influence) effect on the health of crops and the overall prosperity of agrarian societies. These rituals are often conducted on full-moon or new-moon nights. In addition, solstices and equinoxes are considered to have special importance.

It’s important to note here that the Holi bonfire ritual is simple and requires no priest. Unlike the more well-known Hindu sacred fire rituals (Homam or Yajna), the bonfire is not composed of the expensive mango wood and ritualistic ingredients known as “Homa Samagri” but is made up of dry wood collected from broken branches, cow dung cakes, old furniture and household rubbish. Nowadays in semi-urban areas, thin bamboo sticks painted in traditional designs are also sold to be used for the bonfire.

“In Northern India the pile is usually erected on a site east of the village, and consists of a layer of dried cow-dung cakes, the fuel commonly used by the peasantry, on which are placed logs, brushwood, and rubbish.” (Cooke, 1914) [1]

Contrary to popular perception, such simple rituals that can be conducted by anyone are not uncommon in Hinduism and they seamlessly co-exist with the more comprehensive rituals such as Yajnas. This seamless integration of the local, regional, community-specific and the universal rituals is one of the reasons that makes Hinduism, so beautifully diverse.

The Legend of Holika Dahan

While there are many local, regional and deity-specific legends that exist around Holi, the most prominent one is that of the devout child Prahlada. This legend is associated with the Narasimha avatara, one of the ten avatarams of Vishnu, which are described in the Bhagavata Purana (also known as the Srimad Bhagavatam). The legend begins with King Hiranyakashyipu who, through extreme penance, had gained several boons from Lord Brahma and ruled the entire universe. One of the boons he had been granted was that he could be killed “neither at home nor outside, neither during the day nor at night, neither from any known weapon nor by any other thing, neither on the ground or in the sky, nor by any human being or animal” (Srimad Bhagavatam 7.3 v36-38). Hiranyakashipu, convinced of his invincibility, full of ego, greed, jealousy and self-certitude, ruled tyrannically over all three realms and prohibited anyone in the kingdom from worshipping anyone but him.

As his subjects reeled under this persecution, Hiranyakashyipu’s young son, Prahlada, ignored his father’s egomaniacal diktats and continued to worship Lord Vishnu. Angered by his son’s defiance, Hiranyakashyipu tried to dissuade Prahlada by sending him to school, where his loyalists attempted to brainwash Prahlada into accepting the supremacy of his father. But Prahlada, well-versed in the teachings of Sri MahaVishnu, defeats them in a philosophical debate. Hiranyakashyipu, enraged at this umbrage by his own son, then decided to punish him in a way that would set an example for the universes. So he unleashed all the warriors and demons he had at his disposal, but they all fail to hurt Prahlada.

Sculpture in Changu Narayan Temple, Bhaktapur depicting Lord Narasimha slaying Hiranyakashyipu on his thigh. Little Prahlad can be seen standing on the side | Source: Flicker

“He tried to crush him with an elephant, attack him with huge snakes, cast spells of doom, throw him from heights, to conjure tricks, imprison him, administer poison and subject him to starvation, cold, wind, fire and water and pile rocks upon him, but by none of these means the demon succeeded in putting his son, the sinless one, to death. With his prolonged efforts having no success he got very nervous.” (Srimad Bhagavatam, 7.5 v43-44)

Finally, Hiranyakashyipu enlisted his sister, Holika, to help him kill his son. Holika, too has been granted a boon from the Gods, a cloak that protects the wearer from being burned by fire. Obeying Hiranyakashyipu’s command, Holika lured her young nephew to sit on her lap as she sits on a pyre. But as the fire starts raging, the wind blows the cloak from Holika to Prahlada. Thus, by the blessing of Lord Vishnu, the evil aunt is burned in the fire instead of the innocent child.

Eventually, after all other attempts to kill his son Prahlada fail, and the child’s devotion and fearlessness begin to influence other subjects, Hiranyakashyipu decided to take matters in his own hands and attempts to strike the unarmed child with his sword. The sword misses and hits a pillar instead. From this pillar emerges Lord Narasimha, the half-man, half-lion avatara of Vishnu. A fearsome battle ensues, and Lord Narasimha eventually puts Hiranyakashyipu on his thigh at dusk in the threshold of the palace, killing him with his bare claws to save his ardent devotee Prahlada.

Holika’s attempt to kill Prahlada is often linked to the bonfire ritual in Holi. The bonfire symbolizes the fire that protected the good (Prahlada) from evil (Holika).

Celebration with Colours - “Badi Holi”

On the second day of the festival, also known as “Badi Holi” or “Dulendi”, people transcend all boundaries of class, caste, gender, language, and creed, and gather together to play with colored powder (and colored water). Applying colors is considered auspicious on Badi Holi, and so the day begins with all members of the family applying tilakam to the Gods and to each other, including pets and even house plants. Holi is an inclusive celebration – it is believed that no one should be left out of this auspicious festival. People play with colors alongside total strangers on the street, accompanied by dancing and partaking of snacks. Often, groups of young children go around the neighborhood from house to house (not unlike Halloween in America), playing with members of each family. This underlines the festival’s role as a tradition where all bygones are forgiven and forgotten. The adults, too, have their own celebration which is often associated with reckless abandon. Men and women play with each other, laughing, singing, and dancing.

In fact, the reckless abandon and rejection of social boundaries during Holi was one of the things that quite irked the British colonialists about this festival not only in India, but also in colonies where large Hindu populations were enslaved on plantations under the oppressive system of indentured labor, such as Fiji.

“On the day of Holi or Phagua, bands of women roamed the countryside until noon, showering men with a red fluid meant to represent blood. . . . being their only period of license during the long year, the women made the most of it. By midday, unpopular overseers looked like what happened on St. Bartholomew's day; the popular were drenched in cheap perfume. From the glimmer of dawn, Lautoka and the estates were overrun by gaggles of excited women and girls out for a good time. With male control absent for the time being, things happened which staggered the godly. The afternoon and evening were different.” (Kelly, 1988)

The late afternoons, as one can imagine, are spent on removing powdered color from one’s body. Indigenous methods include using a paste of wheat- or chickpea-flour, or oil and turmeric (ubatan) to absorb the color from the skin, much like a sponge. In the evenings, people dress up in new clothes, prepare delicious dishes and invite their neighbors, friends, and family for dinner. Holi celebrations are one of the best opportunities for people to connect with family members and friends.

The Diversity of Holi

Rural Holi

Gujhiya, special sweet-meats made for Holi | Picture Credits: Neha Srivastava

In rural and semi-urban areas, Holi brings forth week-long mela (or fête) which feature indigenous sweet treats, clothes, and indigenous entertainment. Everyone, young and old, male and female, participates in the mela, which provides a major boost to the local economy, especially for nomadic tribes that specialize in folk storytelling through dances, songs and musical plays. Entire villages are decorated for the festival and stay vibrant for days in advance. Rural (and semi-urban) households begin preparation for Holi for weeks in advance. A wide variety of snacks and sweet-meats such as chips and papad (made of pulses, millets, potato and sago) are prepared. A special semi-circular sweet-meat made for Holi, called gujhiya, and other special delicacies are prepared with great enthusiasm and excitement.

Tribal Holi

Holi is the primary festival for most tribes from the northern states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, as well as the western border states of Rajasthan and Gujarat. For some, it is perhaps even more important than Diwali, the other major Hindu festival. For many of the nomadic tribes such as the Banjara tribe of Rajasthan, Holi marks the festival during which they return to their native villages for celebrations and practice traditional dances and prayers to local and community deities. Many of these tribes also have local legends associated with the Holi bonfire in addition to the legend of Holika.

The Laman Banjara tribe of Rajasthan

“During the Holi, two young boys or Geria, are selected as principle Geria. They lead the song and dances. Drinking and merrymaking continues the entire night. In the morning, atleast one man from every house takes a garland of cow dung cakes and places it on the Holi pyre. After this, the Naik commands the lighting of the Holi (a symbol of the demon). Pitr Puja or ancestor worship too is also done in the early morning. After the Holi pyre is kindled, the men folk return to their homes. In the evening, sweets, sheera, kheer and coconut etc. are thrown in the Holi fire by the women. The women blow their tongues and make a sound.” (Burman, 2010)

After the Holi bonfire is lit, a ceremony called Dhund is performed during which women Lengi songs are sung.

Banjara tribals dance at Mandwa pathan Tanda, Ambajogai, District Beed

Created By : Sanjay Jadhav (naik)

Like most tribes of India, the Laman Banjara tribe primarily worships Shakti, or the Divine Mother. Any celebration is incomplete without praying to the Goddess but especially because harvest festivals are associated with fertility and prosperity, appropriately, the divine Mother is worshipped during this day. For the Lamar Banjara tribe, that goddess is Hingala Mata, which they often refer to as Holi mata.

Lamani Banjara women in full traditional attire performing their traditional songs and dances. Source: Pinterest

It is to be noted here that while Hingala Mata is called Holi Mata, this deity is not the same as the demoness Holika, since the same tribe also “burns the demon symbol Holi”. This is a separate entity that has been given a colloquial name in connection to the festival. (This is a critical distinction that will surface again in a later section.)

The Bhil tribe of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh

Bhil tribals in Bakhatgarh village dancing during the colourful Bhagoria festival, which celebrates the kharif harvest just prior to Holi in spring | Source: RuralIndiaOnline

Holi for the Bhil tribe, includes a unique celebration, which includes match-making fairs. For this nomadic tribe, the “eight days leading up to Holi has weekly haats transforming into match-making fairs called Bhagoria where men and women pick prospective partners. Weekly haats, or rural markets, transform into match-making fairs called Bhagoria in the run-up to Holi, when men choose a prospective partner by applying gulal, or red powder, on her face. If the woman likes him, she smears his face red too; if she doesn’t, she wipes off the colour and both move on. Partnerships are sealed with the couple eating paan, after which they elope. ...Holi is the biggest festival among the Bhils and Bhilalas, who for generations have celebrated the end of the harvest with their extended family and friends from other villages at the haat, which became an opportunity to choose a partner from the larger community,” said Soubhagya Ranjan Padhi, professor and head of tribal studies at the Indira Gandhi National Tribal University in Amarkantak town in the Anuppur district in Madhya Pradesh.” (Sharma, 2018)

For the tribals of Kumaon area

Kumaoni Tribal dance during Holi festival | Source: RailYatri blog

“In Kumaun, in the lower Himalayas, a middle-sized tree, or a branch of a large tree, is cut down and stripped of its leaves, each clan having a tree of its own. Young men of each clan beg scraps of cloth, known as Chir, from which the tree gains its name, and these are tied to it. A fire is lighted near the tree, and on the last day of the feast an astrologer fixes a lucky time for the burning of the tree. After it is burned the people leap over the ashes, believing that in this way they get rid of itch and other skin diseases. While the tree is burning there is a contest between members of the various clans, each striving to carry off a piece of the cloth from the tree of another clan. It is supposed to be lucky to succeed in doing this, and a clan which loses a rag in this way is not permitted to set up their tree until the insult is avenged. By another account from the same region, on the IIth day of the month Phalguna, known as "Rag-binding Day " (Chirbandhan), people collect two small pieces of cloth from each house, one white, the other coloured, and offer them to the Sakti, or consort of Bhairava, an old earth god. Then they take a pole, split at the top, so as to admit of two sticks being placed transversely at right angles to each other, and from these the rags are hung. The pole is planted on a piece of level ground, and the people move round it, singing the Holi songs in honour of Krishna and his cowherd girls, the Gopis. On the last day of the feast this pole is burned.” (Crooke, 1914)

The unique Holi celebrations of North Indian tribes is a topic vast enough that can cover an entire book, if not several volumes! These are simply some illustrative examples. Other noteworthy tribal celebrations of special interest can be the Navsari tribe of Gujarat area or the Nata nomadic tribes that have beautiful story-telling traditions through song and dance. Some comprehensive sources of the various tribal rituals can be found in the reference section of this article.

The wide diversity of Holi traditions across North India’s rural and tribal hinterlands is often overshadowed by the more urban representation depicted by Bollywood and other urban pop-culture references that often cater to the sensibilities and tastes of the urban, suave crowds. To many unfamiliar with the tradition, the western-style parties of mirthful youngsters dancing, drinking and playing with colors in well-groomed lawns or rooftops, often becomes the quintessential image of Holi. This overshadowing, understandably, leads to wild generalizations which find its way into the internet, and sadly even academic commentaries on the festival.

However, we would do well to remember, that most of India is still rural and their beautiful unique traditions are more authentic and representative of Holi that the relatively recent urban experience.

CONTINUE READING

—

References

[1] Crooke, W. “The Holi: A Vernal Festival of the Hindus.” Folklore, vol. 25, no. 1, 1914, pp. 55–83. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1255349

[2] Sri Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasadeva. “Srimad Bhagavatam (Bhagavata Purana).” Apple Books. http://www.srimadbhagavatam.org/index.html

[3] Kelly, John D. “From Holi to Diwali in Fiji: An Essay on Ritual and History.” Man, vol. 23, no. 1, 1988, pp. 40–55. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2803032

[4] Burman, JJ Roy. “Ethnography of Denotified Tribe: The Laman Banjara”, Mittal Publications, 2010, pp. 84-85 https://books.google.com/books?id=Ai57G7ei0tIC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=holi&f=false

[5] Sharma, Sanchita. “Gulal, paan, elopement: The tribal way to Tinder in Madhya Pradesh”, The Hindustan Times, Mar 02, 2018

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Neha Srivastava

Neha is an activist and a bi-lingual writer who writes on socio-political issues by passion and an engineer by profession. Her articles have been published in various print and web platform. With Dharma as her guiding light and Shaktitva as the vehicle, she seeks to forge a space for the voices of Hindu women in the global conversations on women. She is the Founder and President of Shaktitva Foundation

Having discussed the subaltern celebrations of Holi in detail in Part 1 - we will turn our gaze towards some of the most common criticisms raised in context of Holi, with a commitment to decoloniality and not simply “anti-oppressiveness”, which is a classic colonizing weapon and, thus, should be thoroughly investigated and not simply taken to have integrity.